Transistor

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify and switch electronic signals. It is made of a solid piece of semiconductor material, with at least three terminals for connection to an external circuit. A voltage or current applied to one pair of the transistor's terminals changes the current flowing through another pair of terminals. Because the controlled (output) power can be much more than the controlling (input) power, the transistor provides amplification of a signal. Today, some transistors are packaged individually, but many more are found embedded in integrated circuits.

The transistor is the fundamental building block of modern electronic devices, and is ubiquitous in modern electronic systems. Following its release in the early 1950s the transistor revolutionized the field of electronics, and paved the way for smaller and cheaper radios, calculators, and computers, among other things.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] History

Physicist Julius Edgar Lilienfeld filed the first patent for a transistor in Canada in 1925, describing a device similar to a field-effect transistor or "FET".[1] However, Lilienfeld did not publish any research articles about his devices,[citation needed] nor did his patent cite any examples of devices actually constructed. In 1934, German inventor Oskar Heil patented a similar device.[2]

From 1942 Herbert Mataré experimented with so-called duodiodes while working on a detector for a Doppler RADAR system. The duodiodes he built had two separate but very close metal contacts on the semiconductor substrate. He discovered effects that could not be explained by two independently operating diodes and thus formed the basic idea for the later point contact transistor.

In 1947, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain at AT&T's Bell Labs in the United States observed that when electrical contacts were applied to a crystal of germanium, the output power was larger than the input. Solid State Physics Group leader William Shockley saw the potential in this, and over the next few months worked to greatly expand the knowledge of semiconductors. The term transistor was coined by John R. Pierce as a portmanteau of the term "transfer resistor".[3][4] According to physicist/historian Robert Arns, legal papers from the Bell Labs patent show that William Shockley and Gerald Pearson had built operational versions from Lilienfeld's patents, yet they never referenced this work in any of their later research papers or historical articles.[5]

The first silicon transistor was produced by Texas Instruments in 1954.[6] This was the work of Gordon Teal, an expert in growing crystals of high purity, who had previously worked at Bell Labs.[7] The first MOS transistor actually built was by Kahng and Atalla at Bell Labs in 1960.[8]

[edit] Importance

The transistor is the key active component in practically all modern electronics, and is considered by many to be one of the greatest inventions of the twentieth century.[9] Its importance in today's society rests on its ability to be mass produced using a highly automated process (semiconductor device fabrication) that achieves astonishingly low per-transistor costs.

Although several companies each produce over a billion individually packaged (known as discrete) transistors every year,[10] the vast majority of transistors now produced are in integrated circuits (often shortened to IC, microchips or simply chips), along with diodes, resistors, capacitors and other electronic components, to produce complete electronic circuits. A logic gate consists of up to about twenty transistors whereas an advanced microprocessor, as of 2011, can use as many as 3 billion transistors (MOSFETs).[11] "About 60 million transistors were built this year [2002] ... for [each] man, woman, and child on Earth."[12]

The transistor's low cost, flexibility, and reliability have made it a ubiquitous device. Transistorized mechatronic circuits have replaced electromechanical devices in controlling appliances and machinery. It is often easier and cheaper to use a standard microcontroller and write a computer program to carry out a control function than to design an equivalent mechanical control function.

[edit] Usage

The bipolar junction transistor, or BJT, was the most commonly used transistor in the 1960s and 70s. Even after MOSFETs became widely available, the BJT remained the transistor of choice for many analog circuits such as simple amplifiers because of their greater linearity and ease of manufacture. Desirable properties of MOSFETs, such as their utility in low-power devices, usually in the CMOS configuration, allowed them to capture nearly all market share for digital circuits; more recently MOSFETs have captured most analog and power applications as well, including modern clocked analog circuits, voltage regulators, amplifiers, power transmitters, motor drivers, etc.

[edit] Simplified operation

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2010) |

The essential usefulness of a transistor comes from its ability to use a small signal applied between one pair of its terminals to control a much larger signal at another pair of terminals. This property is called gain. A transistor can control its output in proportion to the input signal; that is, it can act as an amplifier. Alternatively, the transistor can be used to turn current on or off in a circuit as an electrically controlled switch, where the amount of current is determined by other circuit elements.

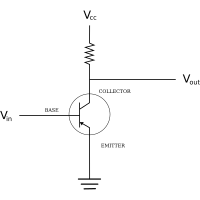

The two types of transistors have slight differences in how they are used in a circuit. A bipolar transistor has terminals labeled base, collector, and emitter. A small current at the base terminal (that is, flowing from the base to the emitter) can control or switch a much larger current between the collector and emitter terminals. For a field-effect transistor, the terminals are labeled gate, source, and drain, and a voltage at the gate can control a current between source and drain.

The image to the right represents a typical bipolar transistor in a circuit. Charge will flow between emitter and collector terminals depending on the current in the base. Since internally the base and emitter connections behave like a semiconductor diode, a voltage drop develops between base and emitter while the base current exists. The amount of this voltage depends on the material the transistor is made from, and is referred to as VBE.

[edit] Transistor as a switch

Transistors are commonly used as electronic switches, both for high-power applications such as switched-mode power supplies and for low-power applications such as logic gates.

In a grounded-emitter transistor circuit, such as the light-switch circuit shown, as the base voltage rises the base and collector current rise exponentially, and the collector voltage drops because of the collector load resistor. The relevant equations:

- VRC = ICE × RC, the voltage across the load (the lamp with resistance RC)

- VRC + VCE = VCC, the supply voltage shown as 6V

If VCE could fall to 0 (perfect closed switch) then Ic could go no higher than VCC / RC, even with higher base voltage and current. The transistor is then said to be saturated. Hence, values of input voltage can be chosen such that the output is either completely off,[13] or completely on. The transistor is acting as a switch, and this type of operation is common in digital circuits where only "on" and "off" values are relevant.

[edit] Transistor as an amplifier

The common-emitter amplifier is designed so that a small change in voltage in (Vin) changes the small current through the base of the transistor and the transistor's current amplification combined with the properties of the circuit mean that small swings in Vin produce large changes in Vout.

Various configurations of single transistor amplifier are possible, with some providing current gain, some voltage gain, and some both.

From mobile phones to televisions, vast numbers of products include amplifiers for sound reproduction, radio transmission, and signal processing. The first discrete transistor audio amplifiers barely supplied a few hundred milliwatts, but power and audio fidelity gradually increased as better transistors became available and amplifier architecture evolved.

Modern transistor audio amplifiers of up to a few hundred watts are common and relatively inexpensive.

[edit] Comparison with vacuum tubes

Prior to the development of transistors, vacuum (electron) tubes (or in the UK "thermionic valves" or just "valves") were the main active components in electronic equipment.

[edit] Advantages

The key advantages that have allowed transistors to replace their vacuum tube predecessors in most applications are

- Small size and minimal weight, allowing the development of miniaturized electronic devices.

- Highly automated manufacturing processes, resulting in low per-unit cost.

- Lower possible operating voltages, making transistors suitable for small, battery-powered applications.

- No warm-up period for cathode heaters required after power application.

- Lower power dissipation and generally greater energy efficiency.

- Higher reliability and greater physical ruggedness.

- Extremely long life. Some transistorized devices have been in service for more than 50 years.

- Complementary devices available, facilitating the design of complementary-symmetry circuits, something not possible with vacuum tubes.

- Insensitivity to mechanical shock and vibration, thus avoiding the problem of microphonics in audio applications.

[edit] Limitations

- Silicon transistors do not operate at voltages higher than about 1,000 volts (SiC devices can be operated as high as 3,000 volts). In contrast, vacuum tubes have been developed that can be operated at tens of thousands of volts.

- High-power, high-frequency operation, such as that used in over-the-air television broadcasting, is better achieved in vacuum tubes due to improved electron mobility in a vacuum.

- Silicon transistors are much more vulnerable than vacuum tubes to an electromagnetic pulse generated by a high-altitude nuclear explosion.

[edit] Types

Transistors are categorized by

- Semiconductor material: germanium, silicon, gallium arsenide, silicon carbide, etc.

- Structure: BJT, JFET, IGFET (MOSFET), IGBT, "other types"

- Polarity: NPN, PNP (BJTs); N-channel, P-channel (FETs)

- Maximum power rating: low, medium, high

- Maximum operating frequency: low, medium, high, radio frequency (RF), microwave (The maximum effective frequency of a transistor is denoted by the term fT, an abbreviation for "frequency of transition". The frequency of transition is the frequency at which the transistor yields unity gain).

- Application: switch, general purpose, audio, high voltage, super-beta, matched pair

- Physical packaging: through hole metal, through hole plastic, surface mount, ball grid array, power modules

- Amplification factor hfe (transistor beta)[14]

Thus, a particular transistor may be described as silicon, surface mount, BJT, NPN, low power, high frequency switch.

[edit] Bipolar junction transistor

Bipolar transistors are so named because they conduct by using both majority and minority carriers. The bipolar junction transistor (BJT), the first type of transistor to be mass-produced, is a combination of two junction diodes, and is formed of either a thin layer of p-type semiconductor sandwiched between two n-type semiconductors (an n-p-n transistor), or a thin layer of n-type semiconductor sandwiched between two p-type semiconductors (a p-n-p transistor). This construction produces two p-n junctions: a base–emitter junction and a base–collector junction, separated by a thin region of semiconductor known as the base region (two junction diodes wired together without sharing an intervening semiconducting region will not make a transistor).

The BJT has three terminals, corresponding to the three layers of semiconductor – an emitter, a base, and a collector. It is useful in amplifiers because the currents at the emitter and collector are controllable by a relatively small base current."[15] In an NPN transistor operating in the active region, the emitter-base junction is forward biased (electrons and holes recombine at the junction), and electrons are injected into the base region. Because the base is narrow, most of these electrons will diffuse into the reverse-biased (electrons and holes are formed at, and move away from the junction) base-collector junction and be swept into the collector; perhaps one-hundredth of the electrons will recombine in the base, which is the dominant mechanism in the base current. By controlling the number of electrons that can leave the base, the number of electrons entering the collector can be controlled.[15] Collector current is approximately β (common-emitter current gain) times the base current. It is typically greater than 100 for small-signal transistors but can be smaller in transistors designed for high-power applications.

Unlike the FET, the BJT is a low–input-impedance device. Also, as the base–emitter voltage (Vbe) is increased the base–emitter current and hence the collector–emitter current (Ice) increase exponentially according to the Shockley diode model and the Ebers-Moll model. Because of this exponential relationship, the BJT has a higher transconductance than the FET.

Bipolar transistors can be made to conduct by exposure to light, since absorption of photons in the base region generates a photocurrent that acts as a base current; the collector current is approximately β times the photocurrent. Devices designed for this purpose have a transparent window in the package and are called phototransistors.

[edit] Field-effect transistor

The field-effect transistor (FET), sometimes called a unipolar transistor, uses either electrons (in N-channel FET) or holes (in P-channel FET) for conduction. The four terminals of the FET are named source, gate, drain, and body (substrate). On most FETs, the body is connected to the source inside the package, and this will be assumed for the following description.

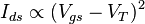

In FETs, the drain-to-source current flows via a conducting channel that connects the source region to the drain region. The conductivity is varied by the electric field that is produced when a voltage is applied between the gate and source terminals; hence the current flowing between the drain and source is controlled by the voltage applied between the gate and source. As the gate–source voltage (Vgs) is increased, the drain–source current (Ids) increases exponentially for Vgs below threshold, and then at a roughly quadratic rate ( ) (where VT is the threshold voltage at which drain current begins)[16] in the "space-charge-limited" region above threshold. A quadratic behavior is not observed in modern devices, for example, at the 65 nm technology node.[17]

) (where VT is the threshold voltage at which drain current begins)[16] in the "space-charge-limited" region above threshold. A quadratic behavior is not observed in modern devices, for example, at the 65 nm technology node.[17]

For low noise at narrow bandwidth the higher input resistance of the FET is advantageous.

FETs are divided into two families: junction FET (JFET) and insulated gate FET (IGFET). The IGFET is more commonly known as a metal–oxide–semiconductor FET (MOSFET), reflecting its original construction from layers of metal (the gate), oxide (the insulation), and semiconductor. Unlike IGFETs, the JFET gate forms a PN diode with the channel which lies between the source and drain. Functionally, this makes the N-channel JFET the solid state equivalent of the vacuum tube triode which, similarly, forms a diode between its grid and cathode. Also, both devices operate in the depletion mode, they both have a high input impedance, and they both conduct current under the control of an input voltage.

Metal–semiconductor FETs (MESFETs) are JFETs in which the reverse biased PN junction is replaced by a metal–semiconductor Schottky-junction. These, and the HEMTs (high electron mobility transistors, or HFETs), in which a two-dimensional electron gas with very high carrier mobility is used for charge transport, are especially suitable for use at very high frequencies (microwave frequencies; several GHz).

Unlike bipolar transistors, FETs do not inherently amplify a photocurrent. Nevertheless, there are ways to use them, especially JFETs, as light-sensitive devices, by exploiting the photocurrents in channel–gate or channel–body junctions.

FETs are further divided into depletion-mode and enhancement-mode types, depending on whether the channel is turned on or off with zero gate-to-source voltage. For enhancement mode, the channel is off at zero bias, and a gate potential can "enhance" the conduction. For depletion mode, the channel is on at zero bias, and a gate potential (of the opposite polarity) can "deplete" the channel, reducing conduction. For either mode, a more positive gate voltage corresponds to a higher current for N-channel devices and a lower current for P-channel devices. Nearly all JFETs are depletion-mode as the diode junctions would forward bias and conduct if they were enhancement mode devices; most IGFETs are enhancement-mode types.

[edit] Other transistor types

|

|

This article contains embedded lists that may be poorly defined, unverified or indiscriminate. Please help to clean it up to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. (September 2009) |

- Point-contact transistor, first kind of transistor ever constructed

- Bipolar junction transistor (BJT)

- Heterojunction bipolar transistor, up to several hundred GHz, common in modern ultrafast and RF circuits

- Grown-junction transistor, first kind of BJT

- Alloy-junction transistor, improvement of grown-junction transistor

- Micro-alloy transistor (MAT), speedier than alloy-junction transistor

- Micro-alloy diffused transistor (MADT), speedier than MAT, a diffused-base transistor

- Post-alloy diffused transistor (PADT), speedier than MAT, a diffused-base transistor

- Schottky transistor

- Surface barrier transistor

- Drift-field transistor

- Avalanche transistor

- Darlington transistors are two BJTs connected together to provide a high current gain equal to the product of the current gains of the two transistors.

- Insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs) use a medium power IGFET, similarly connected to a power BJT, to give a high input impedance. Power diodes are often connected between certain terminals depending on specific use. IGBTs are particularly suitable for heavy-duty industrial applications. The Asea Brown Boveri (ABB) 5SNA2400E170100 illustrates just how far power semiconductor technology has advanced.[18] Intended for three-phase power supplies, this device houses three NPN IGBTs in a case measuring 38 by 140 by 190 mm and weighing 1.5 kg. Each IGBT is rated at 1,700 volts and can handle 2,400 amperes.

- Photo transistor

- Field-effect transistor

- Carbon nanotube field-effect transistor (CNFET)

- JFET, where the gate is insulated by a reverse-biased PN junction

- MESFET, similar to JFET with a Schottky junction instead of PN one

- High Electron Mobility Transistor (HEMT, HFET, MODFET)

- MOSFET, where the gate is insulated by a shallow layer of insulator

- Inverted-T field effect transistor (ITFET)

- FinFET, source/drain region shapes fins on the silicon surface.

- FREDFET, fast-reverse epitaxial diode field-effect transistor

- Thin film transistor, in LCDs.

- OFET Organic Field-Effect Transistor, in which the semiconductor is an organic compound

- Ballistic transistor

- Floating-gate transistor, for non-volatile storage.

- FETs used to sense environment

- Ion-sensitive field effect transistor, to measure ion concentrations in solution.

- EOSFET, electrolyte-oxide-semiconductor field effect transistor (Neurochip)

- DNAFET, deoxyribonucleic acid field-effect transistor

- Spacistor

- Diffusion transistor, formed by diffusing dopants into semiconductor substrate; can be both BJT and FET

- Unijunction transistors can be used as simple pulse generators. They comprise a main body of either P-type or N-type semiconductor with ohmic contacts at each end (terminals Base1 and Base2). A junction with the opposite semiconductor type is formed at a point along the length of the body for the third terminal (Emitter).

- Single-electron transistors (SET) consist of a gate island between two tunnelling junctions. The tunnelling current is controlled by a voltage applied to the gate through a capacitor.[19]

- Nanofluidic transistor, controls the movement of ions through sub-microscopic, water-filled channels. Nanofluidic transistor, the basis of future chemical processors

- Multigate devices

- Tetrode transistor

- Pentode transistor

- Multigate device

- Trigate transistors (Prototype by Intel)

- Dual gate FETs have a single channel with two gates in cascode; a configuration optimized for high frequency amplifiers, mixers, and oscillators.

- Junctionless Nanowire Transistor (JNT), developed at Tyndall National Institute in Ireland, was the first transistor successfully fabricated without junctions. (Even MOSFETs have junctions, although its gate is electrically insulated from the region the gate controls.) Junctions are difficult and expensive to fabricate, and, because they are a significant source of current leakage, they waste significant power and generate significant waste heat. Eliminating them held the promise of cheaper and denser microchips. The JNT uses a simple nanowire of silicon surrounded by an electrically isolated "wedding ring" that acts to gate the flow of electrons through the wire. This method has been described as akin to squeezing a garden hose to gate the flow of water through the hose. The nanowire is heavily n-doped, making it an excellent conductor. Crucially the gate, comprising silicon, is heavily p-doped; and its presence depletes the underlying silicon nanowire thereby preventing carrier flow past the gate.

[edit] Part numbers

The types of some transistors can be parsed from the part number. There are three major semiconductor naming standards; in each the alphanumeric prefix provides clues to type of the device:

Japanese Industrial Standard (JIS) has a standard for transistor part numbers. They begin with "2S",[20] e.g. 2SD965, but sometimes the "2S" prefix is not marked on the package – a 2SD965 might only be marked "D965"; a 2SC1815 might be listed by a supplier as simply "C1815". This series sometimes has suffixes (such as "R", "O", "BL"... standing for "Red", "Orange", "Blue" etc.) to denote variants, such as tighter hFE (gain) groupings.

| Beginning of Part Number | Type of Transistor |

|---|---|

| 2SA | high frequency PNP BJTs |

| 2SB | audio frequency PNP BJTs |

| 2SC | high frequency NPN BJTs |

| 2SD | audio frequency NPN BJTs |

| 2SJ | P-channel FETs (both JFETs and MOSFETs) |

| 2SK | N-channel FETs (both JFETs and MOSFETs) |

The Pro Electron part numbers begin with two letters: the first gives the semiconductor type (A for Germanium, B for Silicon, and C for materials like GaAs); the second letter denotes the intended use (A for diode, C for general-purpose transistor, etc.). A 3-digit sequence number (or one letter then 2 digits, for industrial types) follows (and, with early devices, indicated the case type – just as the older system for vacuum tubes used the last digit or two to indicate the number of pins, and the first digit or two for the filament voltage). Suffixes may be used, such as a letter (e.g. "C" often means high hFE, such as in: BC549C[21]) or other codes may follow to show gain (e.g. BC327-25) or voltage rating (e.g. BUK854-800A[22]). The more common prefixes are:

| Prefix class | Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|

| AC | Germanium small signal transistor | AC126 |

| AF | Germanium RF transistor | AF117 |

| BC | Silicon, small signal transistor ("allround") | BC548B |

| BD | Silicon, power transistor | BD139 |

| BF | Silicon, RF (high frequency) BJT or FET | BF245 |

| BS | Silicon, نظرات شما عزیزان: ارسال توسط امیر عیوضی آخرین مطالب

|